The Legend of the Three Pines

The Three Pines is an important shamanic site, where the Sara say the veil between the worlds is very thin - a powerful and evocative place — the kind of quiet landmark that carries its own weight of myth, whether remembered or forgotten. Triadic arrangements of trees, especially evergreens like pines, have deep resonance in Sara traditions: the triangle being a symbol of balance or passage, and the pine being a tree of endurance and memory. Twisted branches suggest an enduring struggle with unseen forces — wind, age, or something less material.

It might well be a liminal place — a threshold, a place of transition. In old Sara beliefs, places like that — crossroads, oddly shaped groves, or naturally enclosed spaces — were often seen as points where the boundary between worlds thins. A shaman might sit there to listen to the voices of ancestral spirits or interpret dreams. A child born nearby might have the gift of sight. Travelers might feel watched — or protected.

In the worlds of old Danfelgor and the Sara, this would be the kind of site remembered by elders, marked in half-erased ballads or quiet ritual. A Sara wise-woman might leave offerings there: ash bark, salt, bone. A Danfelgorian scholar might dismiss it in a footnote—“a curious local belief in tree-spirits...”— and yet avoid walking through it alone at dusk.

The Three Pines is regarded as the most powerful shamanic site after the Cypress Grove near the Cormorant Lake.

Professor Doktor Renate Schoenbein

The Legend of the Three Pines: The Shaman’s Prophecy

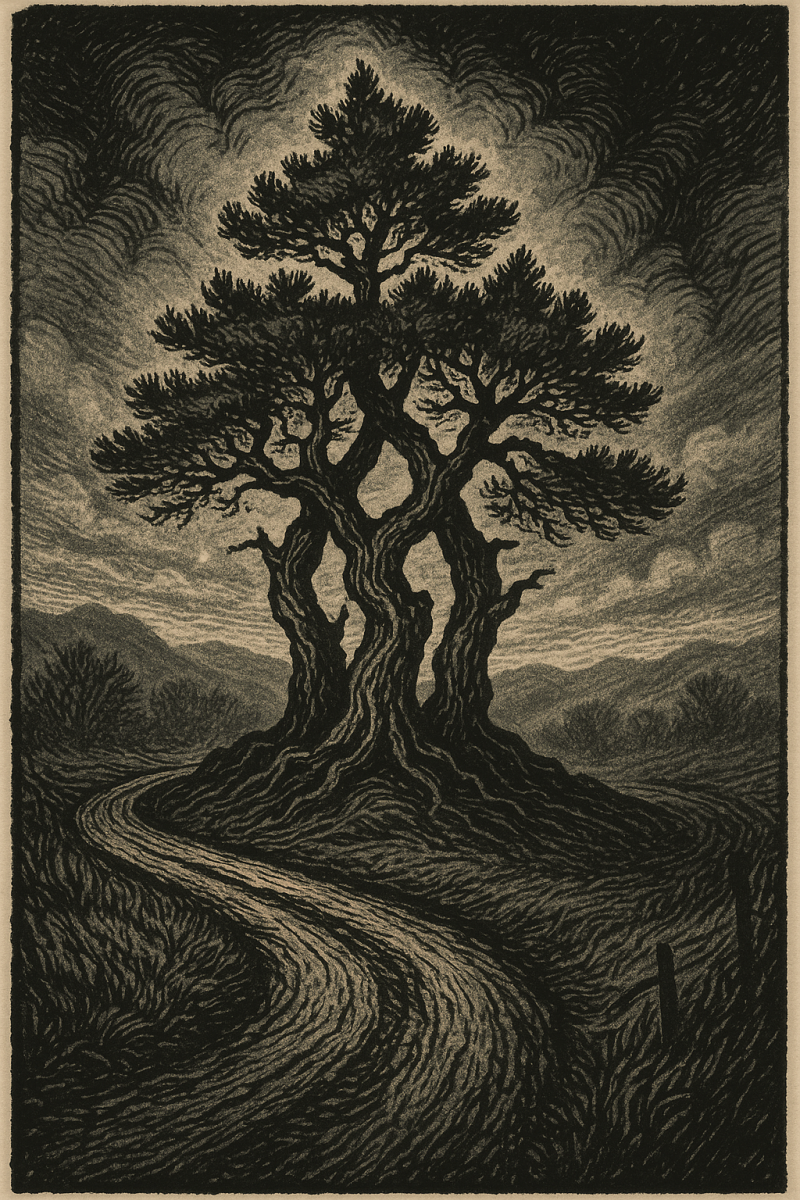

The woodcut illustrations are from a much later telling of the legend, which does vary slightly from the version here

The road that led from Danfelgor to the northern hills was not much more than a pony track — dry and stony in summer, churned to mud in the rains. But in late spring, when the first thistles bloomed and the skylarks hovered above the moors, it became a thing of quiet beauty.

Two young women made their way along it, the wind lifting their cloaks and the scent of crushed pine needles beneath their boots. They were not dressed for a pilgrimage, nor did they come seeking visions — at least not knowingly. One carried a satchel of notes and a half-finished philosophical treatise, whilst the other wore bracelets made of dyed thread and carved bone. They laughed and argued as they walked, pausing now and then to share a drink of spring water or point up to a bird overhead.

One was called Aelis, daughter of a well-respected magistrate of Danfelgor - raised in the courts and cloisters, she had studied the writings of Kentomirto, the city’s great philosopher, since childhood. She saw the world as a swirling mix of ethics and intentions, and believed reasoning and meditation could lead souls to peace.

The other was called Tirna, a fisherman’s daughter from the docks of Danfelgor, whose mother had had Sara blood. Her grandmother had told stories of the spirits of wind and stone, and lit candles to Zania on the river’s edge. She had come to the city with her family some years before but had never quite felt at home in its marble logic.

They had met by chance at the Herring’s Misfortune, a bohemian tavern near the city’s library, where Tirna played and sang, and Aelis liked to debate with student poets. Friendship followed, born of shared curiosity about the world.

Neither of them knew why they had come to the hills that day. Aelis had spoken of getting some fresh air, Tirna of a dream about a place with twisted trees and whispering light filtering down through branches. And so, they had wandered until they came to the Three Pines which stood at the edge of a low rise, in a triangle around an outcrop of rock. Their trunks were thick and gnarled, branches bent like old arms raised toward the sky and the wind seemed to hush as it passed through them, as though the trees were somehow listening.

Aelis stopped. “It’s strange. I’ve seen many trees, but none quite like these.”

Tirna nodded slowly. “This is the place - I remember it now from the dream.”

Then they saw — or rather felt, in a stillness that pulled at the senses, as if time had paused - a man who sat cross-legged between the trees, robed in patchwork hides and grey cloth. His hair was the color of ash bark, long and braided, and his eyes were so dark they seemed bottomless.

“I was expecting you,” he said.

Neither of them spoke at first.

“You were expecting someone,” Aelis said cautiously. “We could just be travelers.”

“Even travelers are drawn by deep, unseen currents” the man replied, not unkindly. “And some roads only appear when the time is right.”

Tirna took a step forward. “Are you a holy man?”

“I am what remains - just that,” he said. “A watcher of crossing paths. I am Mornaheido.”

Aelis folded her arms. “And what is it we’ve crossed into?”

Mornaheido looked at her gently. “The place between — between what was and what will be. Between reason and instinct. Between the fire of thought and the water of spirit. Where the pony road crosses the ghost road”

He gestured for them to sit - the air beneath the pines felt strangely warm, though the sun had vanished behind a bank of clouds.

“What do you seek here?” he asked.

Neither had a ready answer.

Tirna glanced at Aelis. “I… don’t know. Not yet.”

Aelis hesitated. “Understanding, I suppose. Of how to live rightly. Of what path to take.”

Mornahiedo nodded. “Then listen.”

And so they listened. And in the hours that followed, as wind sighed through needles and dusk gathered at the edges of the clearing, Mornaheido the shaman spoke of things long hidden — of the old gods and the new wisdom, of the fire that knows form and the river that knows change. He spoke of the river-daughter Zania and the quiet power of stillness. Of Vazendafur, the Storm Father and the echoes of his name in the ancient stones. He spoke of balance — not between opposites, but within them. And in the end, when the stars had begun to appear, he spoke to them their futures, though neither fully understood.

“To the one born of thought,” he said, turning to Aelis, “you will wield no sceptre, but kings will heed your words. You shall write what cannot be spoken.”

“And to the one born of the river,” he said to Tirna, “your song shall awaken the city, though you will not live to hear the end of it. A mother to many who are not your own.”

They sat in silence for a long while, until Mornaheido closed his eyes and seemed to fade into the shadow of the trees. The wind rose and the needles stirred. Later that evening, the two young women, changed in ways they could not yet name, began their journey back to Danfelgor.They said very little as they descended the hills. The road back to Danfelgor had not really changed — it was still rough, winding, scored by cart wheels and flanked by silvergrass — but it felt different now. They walked side by side, but each was deep in her own thoughts.

Back in the city, Aelis returned to her father’s house near the Law Courts, but found herself increasingly restless in its corridors. She resumed her studies, met her tutors, and debated in the marble halls where philosophy students gathered. But when she read Kentomirto now, she noticed things she had not before — the spaces between his words, the quiet assumptions beneath the logic, and she began to ask uncomfortable questions.

She drafted an essay called “On the Mirror of the Self in River and Flame”, which caused quiet murmurs in the university. In it, she proposed that true harmony required not only rational mastery, but an acceptance of what lay beyond the reach of reason — the ancestral memory, the spiritual rhythm, the "knowing without naming" that the Sara spoke of.

Older philosophers dismissed it as “the poetry of a confused young woman.” But others — younger, sharper — began to listen. Her writing began to circulate outside the courts, down through the city’s quarters, into the hands of students, artisans, even guild masters. And one night, a quiet figure in dark robes left a small paper-wrapped bundle on her doorstep - a piece of river-polished stone, carved with a symbol of Zania.

Tirna returned to the dockside quarter to find her aunt ill and her cousins worried. She stayed to help, walking to the fishmarket in the mornings and playing and singing at the Rusty Anchor in the evenings. But her music was different now - where once she played lively reels or love songs, she now wove melodies filled with longing, mystery, and the pulse of ancient things. She sang of rivers that dreamed and of stones that whispered. Her voice — raw, imperfect, but full of soul — began to draw people in. Not just rivermen and barmaids, but students, scribes, even an off-duty city guard or two.

Old riverfolk said she reminded them of the way songs used to be, before the city grew cold and clever. She refused to sing in the higher-class taverns, though she was invited. “This voice belongs to the stone and the reed,” she said. “Not to the tiled floors of the Cargo Inn.” But word of her songs reached farther than she knew. A merchant's daughter quoted one of her verses at a wedding. A stonemason carved another into a gatepost. And late one night, after the Anchor had closed, a stranger left her a note that read:

"There is power in you. But beware — it stirs things that sleep."

The two women saw each other rarely after their return, but neither forgot the Pines. In council chambers, Aelis began to argue that the Dual Monarchy should recognize not just the Sara culture, but the living wisdom of their beliefs - not simply as political appeasement, but as spiritual necessity — a unification of the dual truths that had been divided long ago.

Tirna, meanwhile, was invited to perform at a spring festival honoring the River Danfel. The invitation came with a seal she didn’t recognize. When she arrived, she found a gathering of both Danfelgorian nobles and Sara elders — something that only happened rarely. And there, seated near the front, was Princess Pellae, wearing the ring of her mother — the one given by Zania, daughter of the river god.

Tirna sang a song she had dreamed the night before, and the whole city seemed to listen. Her voice seemed to carry through every alley, every market square, every open window. Aelis, watching from a distance, recognized the lyrics. They were lines from a poem she had written but never published. And at that moment, they both remembered Mornaheido’s words beneath the trees.

“You shall write what cannot be spoken.”

“Your song shall awaken the city, though you will not live to hear the end of it.”

For years, the Dual Monarchy had seemed stable - the city of Danfelgor prospered, Estasean trade flowed freely, the Sara clans, once fragmented, were united. Yet beneath this calm, ancient currents stirred — some spiritual, others dangerously political. It began with a proposal — bland in appearance but sweeping in implication. A radical group of monks, scholars and over-pious merchants drafted a “Unification Edict” aimed at harmonising religious practices across the Dual Monarchy. They cited reason, order, and the writings of Kentomirto to justify a gradual phase-out of “folk rituals” and “spiritist superstitions.”

In effect, it would mean the outlawing of certain Sara rites, a ban on river-offerings to Zania, Linadafur, and the old gods, and a rewriting of educational texts to omit references to spiritual matters not sanctioned by the city’s philosophers. The authors insisted it was for peace but the truth was darker. In reality they feared the growing influence of the old beliefs — particularly among the artisan class, poorer river folk, and even parts of the minor nobility. They feared what they could not control, and so they feared Aelis and Tirna.

After reading the edict, Aelis went to the Stone Court and spoke for three quarters of an hour without notes, weaving law, philosophy, and history into a single, burning thread:

“You fear what is older than your words. You fear what you cannot tax, censor, or codify. But this flame is not foreign — it is ours. We were not made by reason alone. The Danfel flows with mystery, and so do we.”

Her words were met with silence, then shouts — some of praise, but more accusing her of inciting disorder. Her lectures were suspended and a warrant for her detention was drawn up, but unsigned. For now.

Goraka Pellae, when she was informed by a source at court, quickly intervened, and summoned Aelis to the palace gardens, beneath the cypress tree that overlooked the river. There, Pellae showed her the ring.

“Zania spoke to Valubani in the deep river. I wear this not as ornament but as a reminder. The old gods are not dead. They are quiet — for now.”

Aelis bowed low. “Then you believe as I do.”

Pellae looked westward, toward the hills. “I believe far more than that, child…”

Tirna received an invitation, sealed with a wax seal shaped like a pine cone, which led her to a gathering at the Herring’s Misfortune, a bohemian tavern near the Library, where artists, heretics, and free thinkers met. There she sang again — but this time her music was accompanied by stories from Sara women, dock-hands, and others who had felt the sting of the erasure of their culture. The crowd wept, laughed, and shouted. But Gitcni’s spies were watching, and a few nights later, Tirna was warned — by a guard whose daughter she had once helped — that she was to be arrested under suspicion of sedition. Instead of waiting for the knock on her door, she vanished.

For weeks, people said she had been taken. Her name was scrawled on walls, sung in alleys. Some thought she had fled the city. Others claimed to have seen her — in taverns, in the market, in dreams. Then one day, during a great procession at the river for the Danfel Festival, a song rose from a hidden place — her voice, unmistakable, singing from within the crowd. A hush fell and all eyes turned to Princess Pellae, who stood upon the barge in ceremonial robes and raised her hand as if to stop the music. But instead of ordering silence, she lifted her voice and joined the song. The monks and nobles froze, but the river folk — and many others — sang with her.

“One shall write what cannot be spoken.

One shall awaken the city with song.

And one shall wear the Danfel ring and reconcile the fire and the flood.”

In the weeks that followed, the edict was quietly shelved. Aelis was reinstated and Tirna returned in daylight, flanked by supporters who now protected her - Pellae commissioned a new monument to the union of flame and river, reason and mystery. It stood in the square between the philosophers’ courts and the fishmarket. At its centre, carved into a massive stone brought from Greyfell, were three pines, their branches twisted to form a circle.

It was just after dawn, on the morning of the autumn equinox, when the drumbeat began. At first, only the market traders setting up their stalls noticed it — a low, steady rhythm echoing across the paving stones of the Great Market Square, like a heartbeat beneath the city. Then came the chant - long syllables drawn out in a Sara dialect few could completely unravel, but which vibrated somewhere deeper than understanding. By the time the sun climbed over the eastern towers, hundreds had gathered around the lone figure sitting cross-legged on a woven rug at the side of the square. His eyes were closed and his drum was painted with pines and rivers, fire and stars., whilst his cloak was stitched with talismans that murmured as he moved. It was the shaman of the Three Pines.

For years, he had remained at the pine grove, receiving visitors in silence and sending them back changed, and had never come to the city or beaten his drum whilst sitting on its stones. But now he chanted, “I walk the ghost road, between the worlds. You are listening — and so are the spirits.”

When Tirna arrived, barefoot and solemn, the crowd parted without being asked. She sat beside him, matching his rhythm on a small hide-drum she had carried as a girl. Then Aelis came, bearing a scroll she did not open, and knelt. And then, Mirana, the Kentomirtoan nun whose voice soothed even the harshest magistrates, walked slowly to them and stood in silence — eyes closed, hands clasped. The crowd watched, silent now as some wept without knowing why. Then the shaman opened his eyes — a startling green, sharp as new leaves.

“One shall write what cannot be spoken,” he said, looking to Aelis.

“One shall awaken the city with song,” and he smiled at Tirna.

“One shall wear the ring and unite the fire and the flood.”

And then Pellae entered the square and stepped down from her palanquin, her robes river-blue. On her hand shone the ring — her mother’s ring. She walked without guards and took Tirna’s hand, then Aelis’s, and they then took Mirana’s hand - she did not hesitate before joining the ring of hands. Then the shaman stood — tall now, voice clear.

“Trust is a bridge across the River - remember what Kentomirto preached here about the River. Unity is the fire that feeds all hearths and all hearts. The old gods are not gone, but only silent for a time. The true Path neither does forget, nor is forgotten.”

He began to chant a three note melody, one that seemed to rise from the stones themselves. The four women joined in, and then the crowd and then the market stalls and the balconies and walkways above, until it seemed the whole city sang. When a group of stern Kentomirtoan monks, robed in grey, tried to read out the Edict from a scroll, they were booed and jeered, their voices drowned by the people. The Master of the Craftsmen's Guild stood in the middle of the market and called out in a strong, clear voice,

"United by river and land, Sara and Danfelgor shall walk together as kin, and stand fast against all our trials. These over-zealous monks shall never divide us - our unity makes us strong."

The monks and their few supporters left the square hurriedly, scared by the crowd's reaction.

Years later, an old woman sat on a bench in the morning shade of the Central Market, the sun just brushing the high stepped gables of the buildings that surrounded the square. Her granddaughter swung her feet back and forth and said:

“But did it really happen, Mami? The singing? The prophecy? The fire that didn’t burn?”

The woman smiled, brushing a wisp of white hair from her face.

“I was there, child. I remember it all.”

She pointed to the stone at the center of the square, carved into three pine trees.

“The shaman came and beat his drum, and the whole market stood still. The nun stood beside the princess as the scribe and the singer stood side by side, and for a moment, Danfelgor breathed as one body.”

The girl’s brow furrowed.

“And what happened afterwards?”

The old woman’s eyes grew distant.

“The next morning,” she said softly, “before the sun had fully risen, the Gorak himself walked into the square. No guards or banners.”

“Who?”

“King Valubani, the Gorak of Danfelgor and the Ouaq - our King and the Great Khan of all the Clans - he stood on the very spot where the shaman had sung.”

The girl leaned in.

“And?”

“And Valubani said this, in a loud voice -

‘All that happened here yesterday has been reported to me, and for the avoidance of doubt I say this unto you all.

As I, your Gorak, am Sara, and as the Goraka Pellae is Danfelgorian, as we are united in the Dual Monarchy, in our love for each other and in our respect for each other’s beliefs and cultures, so the Sara and Danfelgor are united now and for all time. The Edict is no more, and may not be read out in public places again.

I have spoken.’”

The girl was quiet for a moment. Then she asked her grandmother,

“Did the monks try to boo him?”

The old woman chuckled.

“No, little one. You never saw Valubani when he was angry - even the monks knew to keep quiet and listen that day.”

She reached down and handed her granddaughter a small wooden pendant carved with three trees.

“One day you’ll come here alone. And maybe, when the wind is right, you’ll hear the shaman’s drum.”

The girl clutched it tightly.

“Will I know?”

“When the time is right, you will know, I promise. You will know.”

The Legend of the Three Pines

There is a place some of the older people still whisper about — an old place, older than borders or kings, older even than names. Three pine trees stand in a crooked triangle where a narrow pony track bends like a thought left unfinished. Their branches twist as if reaching for something unseen, and the air beneath them hangs heavy and hushed.

Long before any road cut its way through the hills, before Danfelgor sent out its taxmen and scribes, the land had a language of its own — not of words, but of wind and branch and stone. The Three Pines were part of that speech.

They do not grow like ordinary trees. Their trunks lean inward, slightly, as if conferring. Their bark is furrowed not just by weather, but by something older — a pattern like a script that no one living can read. Birds avoid them and animals skirt their roots. In spring, snow sometimes lingers in their shade and in winter, a hush falls thick around them, as if time forgets to pass.

The locals say they mark a breach or seam — a place where the fabric of this world wears thin. There are stories of old women leaving bread between the roots for absent friends, of children who sleepwalked there and returned with songs in strange tongues. There are no offerings now, only silence, but some remember.

Among the Sara, it is said the Pines were once guardians of a ghost road used by shaman to travel between worlds.They call it “Where the Ghost Road crosses the Pony Road”. In Danfelgor, few speak of it any more, but a few old philosophers claim the Pines are part of a “liminal geography” — a place of intersection where belief, memory, and reality become mutable.

No marker stands - no shrine - only that triangle of earth, and the bridle path that passes through it. It was there, in the long shadow of afternoon, that three travelers came upon each other - none had expected company but each of them had a reason for walking alone.

Elsha was a healer and herbalist, escaping her village’s suspicion after a child died in her care. Nereth was a former soldier turned drifter, whose dreams were haunted by fire and voices she could not forget. Callun was a student from Danfelgor, walking away from a failed apprenticeship in the College of Law. They met as strangers at the Three Pines, and something — a flash of silver, a cry in the distance, a glimpse of a fourth figure darting through the trees — shattered the stillness between them. Later, when questioned in the village inn, each would tell a different story.

Elsha came walking with a satchel of dried herbs, and she wasn’t certain why her feet had taken her toward the Three Pines, except that when she reached the fork in the road above the valley, her heart had started beating like it did when a storm came in fast off the sea. She’d heard the stories - her grandmother had called the place "the Crossroads Without a Gate." But Elsha had never believed in that kind of thing. Her work dealt with fevers, childbirth, slow-growing cancers—earthly things with smells and weeping.

But lately, she had started seeing things in dreams - a woman wrapped in shadow, standing between pines, whispering something Elsha could never remember upon waking. A name she once knew, a face she once touched, and the dream that wouldn’t leave her — someone calling for help who she had failed.

So she went on and when she reached the Pines, she stopped and her hand trembled as she laid her satchel down and heard the flute. Just a low, wavering sound - not tuneful, or even good, as it drifted through the trees. She followed the sound and came upon a young man sitting cross-legged, back against one of the pines, eyes closed.

When he stopped playing, he opened his eyes — blue as the sky and just as distant — and said:

“You heard her too, didn’t you?”

She didn't ask who. Because she had.

Callun didn’t have a name when he left the hills. He’d had one once, but it was given to him by the people who’d locked doors and turned him away when his mother was coughing blood. The girl he loved had died in the same plague, and the elders said it was his fault for touching her when the moon was full. So he wandered, carrying little but his cane flute. The dreams had grown stronger of late - dreams of a tree with three faces and a shaman’s voice saying “This is not the end, only the folding.”

When he started to ask what that meant, he’d wake from the dream. The flute had been his mother’s, though she very rarely played it, and kept it wrapped in a scarf that smelled of lavender. Callun taught himself to play and when he played, the pain quieted. When he played beneath trees, it felt like something else listened, so he followed the dreams south, toward the Danfelgorian border, into the hills where no one knew his name. One day he climbed a ridge and saw the Three Pines for the first time.

They weren’t tall, but they bent as if wind had shaped them from within. They made a triangle, and at the center stood a black stone overgrown with moss. The air shimmered faintly, like it did before lightning. He sat beneath one of the pines, lifted his flute, and played the notes from his dream. And that’s when the healer arrived, with dusty boots and wary eyes. She looked as though she’d spent her life trying to believe in things too reasonable to be true. He stopped playing when he felt her gaze.

“You heard her too, didn’t you?” he asked.

She nodded. And just then — the faintest crunch of boots. Someone else was coming.

Nereth had been born among the hawk-eyed caravan traders who skirted the salt roads between Estasea and the outlands, she was the daughter of a spice-runner and a woman whose name no one would speak aloud. Her youth was spent between merchant wagon trains, bandit encampments, and forgotten caravanserais. She learned to lie before she learned to read, and to steal before she could write her name, but it was not thievery that had brought her to the Three Pines.

It was a voice — low and unfamiliar, in a dream she'd had not once but thrice. A shaman’s voice, clear as glass:

“You carry your blade too close to your soul. Come to where the three shadows fall. Bring what is broken.”

Nereth didn’t believe in omens. She believed in coin, survival, the flick of a blade and the silence that followed. But she also believed in patterns, and when dreams came in threes, she listened. On the morning she crossed into the valley, a raven followed her. She didn’t like it but she carried on and crept low along the ridge until she saw the clearing. The pines, the stone and two figures already there — a thin boy with a flute, and a woman in leathers, eyes wary as hers.Nereth didn’t draw her knife.Yet. She stepped into the clearing, gravel crunching underfoot. The boy’s head turned first.

“You heard her too,” he said, as though she’d already agreed.

The healer straightened. Nereth crossed her arms. “I don’t follow ghosts. But something led me here.”

She looked at the trees — bent, unnatural, watching.

“Who are you two?”

The boy smiled faintly. “I’m Callun. I came for music.”

The healer replied, “I’m Elsha. I came for answers.”

Nereth didn’t answer right away. Then, with a slight shrug: “I came to settle a debt.”

Wind stirred the needles. A low, musical sound echoed faintly — perhaps from the trees, perhaps from deeper within. Callun looked down at the stone in the center. “Maybe we all did.”

The sun had not moved - it hung in the sky like a painted disc as if time at the Three Pines had stretched like wax before the flame. The three stood within the triangle of gnarled trunks, uncertain, each burdened and made silent by a feeling of being called. Then the wind changed - it moved not from the west or east, but seemed to rise within the pines. The raven took flight and the birdsong stopped.

Callun was the first to react. His hands trembled on the flute. He raised it instinctively to his lips, and from it came a three note phrase — one he had never played before but recognized from his dreams.

As the sound hung in the air, Elsha dropped to one knee, clutching the amulet around her neck — a crescent-shaped shard of bone worn smooth by time. It seemed to her that it pulsed with heat, and her mind was filled with the image of her mother’s face — not as she remembered her, but young and fierce. She saw her kneeling beneath these same trees, whispering to the soil, blood on her palms, tears on her face.

Nereth didn’t hear music or see visions - she felt the ground open beneath her. One moment she stood firm, the next she was in a desert under moonlight, standing beside a man she once betrayed. His eyes were sad. He handed her a broken blade — hers, the one she thought lost in the scuffle before he died.

“You carry your blade too close to your soul,” he said softly, echoing the dream. “But now you know where it belongs.”

When the vision passed, Nereth was on her knees, her knife driven into the dirt before the stone. The three looked at one another, but none spoke. A voice rose from between the pines and all at once they saw a ghostly shape, like moonlight on midnight snow, like the spirit of a shaman who had gone over to the spirit world long ago, his arms spread out like an eagle’s wings.

"Three broken paths converge. A wound remains. One must remember. One must forgive. One must choose."

The pines groaned as the stone before them seemed to crack and from within the split, a light shone with the silver clarity of moonlit snow. It rose from the crack, neither flame nor mist and shimmered as it lifted - each of the three felt it differently, through the lens of their own past.

To Callun, the light was sound — pure and deep. It resonated like the final chord of a great song, written not just with notes but with memory. He heard his father’s laughter, the crying of gulls at the coast, and the long silence of frost-bound mornings. It was all one thing — the music that underlay the world. For the first time, he understood that what he played was not merely melody, but invocation. The Three Pines had heard him and had answered.

To Elsha, the light was a path. Not a road of stone or soil, but a thread that connected all things — rivers, bones, dreams, stars — and ran through her own heart like a silver thread. She saw her ancestors walking through a world before names, guiding her steps without her knowing. The old symbols she had seen in Serrin’s ring, the tattoos on Sara elders, the shapes she found burned into driftwood were not remnants, but seeds. Her people had not been forgotten by the land - they had merely gone quiet, waiting until someone would listen.

To Nereth, the light was a witness — not forgiving, not condemning, simply present. She saw all of herself in its glow — the rebel and the killer, the protector and the coward, the child who once wanted peace and the woman who chose knives instead. And still, the light did not retreat. It remained - it knew her and it did not turn away. All three felt the power of it settle in their chests. And then the voice returned.

“One wound remains…”

They saw the land fractured, and belief divided — some clinging to Kentomirto’s calm stoicism, others whispering prayers to river-spirits in the dark. Trade caravans rolled across bridges where once blood had run. In the city of Danfelgor, something ancient stirred.

“One must remember…”

Callun’s flute glowed faintly as he placed it to his lips and played a single, trembling note — and the stone sealed again, the light folding into it like smoke into a jar.

“One must forgive…”

Nereth knelt and pressed her forehead to the stone, then rose, turned her back to it and left her dagger behind.

“One must choose.”

Elsha stepped forward. Her amulet, once bone, had become something clearer like amber. She laid it in the crook of one of the pines and whispered something in the Sara dialect, old words, older than she knew. Then it was done. The light was gone. The spirit shape of the pines’ shaman was gone, and the three pines stood as they had for a hundred years, twisted and wind-blown.

But each of the three travellers walked away changed.

Create Your Own Website With Webador